Where to Draw the Line?

Valley-bottom rivers and streams perpetually migrate and meander within their floodplains (Figure 1). Channels avulse, oxbows are formed and the channel centerline moves through time with the laws of fluid dynamics and physics in a manner both unpredictable but consistently active. With this restless channel movement comes bankline erosion, both a natural process but also a river behavior that has been unwelcome for those who settled, farmed and developed floodplains for human use – typically endeavors that are not well suited to dynamically changing river landscapes. An entire subindustry exists today whose principle focus is to arrest river bank erosion.

Ironically, rivers and streams have been manipulated, trained and/or dramatically changed by human endeavors typically experience bankline erosion rates that accelerate beyond the previous “natural” or “quasi-stable equilibrium” conditions. Accelerated erosion rates are associated with both ecologic and physical channel state changes for rivers. In the cold water regions of the mountain West common impacts of high upstream erosion rates and incoming sediment loads include negative changes to fisheries, water quality, stream ecology and riparian settings. For the most part, accelerated bankline erosion is viewed as a “bad” thing.

During a recent field reconnaissance on the Ruby River in SW Montana, my colleague Karin Boyd (Applied Geomorphology, Bozeman, MT), found ourselves professionally “arguing” about when and where bankline stabilization was warranted in reaches of river that were clearly “unzipping” – i.e. in a state of rapid channel change including both downcutting and lateral channel expansion. Our reason for being there was to assess the potential of these reaches for restoration interventions. A career-long interaction with the Ruby River, from headwater streams to the confluence, have had us scratching our heads over a wide variety of active channel change, recovery, partial recovery and ongoing degradation symptoms in the corridor.

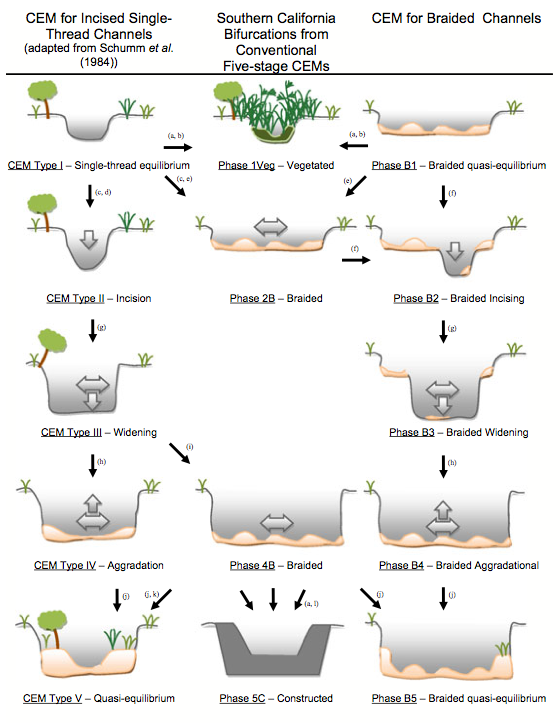

Back to the “argument”. Karin and I regularly have “focused discussions” concerning where a particular reach of river fits within our professional knowledge of typical signatures of changing river systems (Figure 2). Figure 2 is one of many depictions of channel evolution models (CEMs) that are largely based on decades of fluvial geomorphic research and field observation. There are many variations of these models as each river system is unique in terms of its history, (pre-disturbance condition and accumulated human impacts), geology, hydrology, and climate – leaving lots of room for Karin and my geek-fueled arguments. Has the reach turned the corner towards improvement, stuck in time or heading down?

Staring down from the top of a 10 foot vertical bank to the river below, our debate of that day was whether or not this highly altered and incised river reach had evolved to the point where it had carved out a wide enough inset floodplain surface such that the stabilization of outside bend eroding terrace toes was a potential key treatment to accelerate the recovery of the river (Figure 3).

In other words, was it entering the CEM Stage IV zone depicted in Figure 2, where erosion of outside bend terraces, (former floodplain surface), has created enough new floodplain surface area to begin aggrading and potentially stabilizing? I was making the argument that yes, it in fact had reached this stage and we could potentially accelerate the recovery of the channel if we simply stabilized the terrace toes to reduce recruitment of sediment in a river with fine sediment deposition problems down-valley. In my mind, the river was free to migrate away from the terraces from this time forward with a hard line drawn on the terrace toes. Karin of course had some additional observations.

“OK, Scott, but is the river bed at a stable grade yet? I see evidence of continuing incision”. It didn’t take me long at all to agree having her point out her field evidence. Now all of the sudden, the options for restoration intervention in this reach took on a whole new light – which lead to developing a more enhanced suite of strategies to address a complicated situation.

While this blog piece has meandered a bit itself, I’m drawing focus to the typical “if its broken and eroding then stabilize the banks” approach taken by many out there doing bankline work including landowners, agencies, and government interests. There is not a one-size-meets-all strategy for addressing severe bankline erosion and the water quality and natural resource degradation associated with that, be that hard rip-rap or the suite of bioengineered bankline alternatives.

The question always is, “where do we draw the hard bank line” in eroding and incised systems such as these? These reach types are copious throughout the Western US on streams and rivers of all sizes and a scenario restoration professionals confront on a regular basis. If we draw the line in wrong spot or without addressing the bank failure mechanisms in the first place, thousands of dollars of intervention work may be for naught or worse birth unintended consequences.

I’m not saying that bankline stabilization on whole is a bad intervention strategy – but if the answer to stabilize banks or address other systemic problems, (or a combination of both), seems simple, it probably is worth some hearty bankside conversation before committing!